- Home

- Maggie Stiefvater

Wolves of Mercy Falls 03 - Forever Page 4

Wolves of Mercy Falls 03 - Forever Read online

Page 4

She didn’t even hesitate. “Roll him on his side so he doesn’t drown in his own spit.”

“He’s a wolf.”

In front of me, Cole was still seizing, at war with himself. Flecks of blood had appeared in his saliva. I thought he’d bitten his tongue.

“Of course he is,” she said. She sounded pissed, which I was beginning to realize meant that she actually cared. “Where are you?”

“In the house.”

“Well then, I’ll see you in a second.”

“You —?”

“I told you,” Isabel said. “I was thinking of calling you.”

It only took two minutes for her SUV to pull into the driveway.

Twenty seconds later, I realized Cole wasn’t breathing.

CHAPTER SEVEN

• SAM •

Isabel was on the phone when she came into the living room. She threw her purse on the couch, barely looking at me and Cole. To the phone, she said, “Like I said, my dog is having a seizure. I don’t have a car. What can I do for him here? No, this isn’t for Chloe.”

As she listened to their answer, she looked at me. For a moment, we both stared at each other. It had been two months and Isabel had changed — her hair, too, was longer, but like me, the difference was in her eyes. She was a stranger. I wondered if she thought the same thing about me.

On the phone, they’d asked her a question. She relayed it to me. “How long has it been?”

I looked away, to my watch. My hands felt cold. “Uh — six minutes since I found him. He’s not breathing.”

Isabel licked her bubblegum-colored lips. She looked past me to where Cole still jerked, his chest still, a reanimated corpse. When she saw the syringe beside him, her eyes shuttered. She held the phone away from her mouth. “They say to try an ice pack. In the small of his back.”

I retrieved two bags of frozen french fries from the freezer. By the time I returned, Isabel was off her phone and crouching in front of Cole, a precarious pose in her stacked heels. There was something striking about her posture; something about the tilt to her head. She was like a beautiful and lonely piece of art, lovely but unreachable.

I knelt on the other side of Cole and pressed the bags behind his shoulder blades, feeling vaguely impotent. I was battling death and these were all the weapons I had.

“Now,” Isabel said, “with thirty percent less sodium.”

It took me a moment to realize that she was reading the side of the bag of french fries.

Cole’s voice came out of the speakers near us, sexy and sarcastic: “I am expendable.”

“What was he doing?” she asked. She didn’t look at the syringe.

“I don’t know,” I said. “I wasn’t here.”

Isabel reached out to help steady one of the bags. “Dumb shit.”

I became aware that the shaking had slowed.

“It’s stopping,” I said. Then, because I felt like being too optimistic would somehow tempt fate into punishing me: “Or he’s dead.”

“He’s not dead,” Isabel said. But she didn’t sound certain.

The wolf was still, head lolled back at a grotesque angle. My fingers were bright red from the cold of the frozen fries. We were totally silent. By now, Grace would be far away from where she had called from. It seemed like a silly plan, now, no more logical than saving Cole’s life with a bag of french fries.

The wolf’s chest stayed motionless; I didn’t know how long it had been since he’d taken a breath.

“Well,” I said, quietly. “Damn.”

Isabel fisted her hands in her lap.

Suddenly the wolf’s body bucked again in another violent movement. His legs scissored and flailed.

“The ice,” Isabel snapped. “Sam, wake up!”

But I didn’t move. I was surprised by the ferocity of my relief as Cole’s body buckled and twitched. This new pain I recognized — shifting. The wolf jerked and twitched and fur somehow sloughed and rolled back. Paws peeled into fingers, shoulders rippled and widened, the spine buckled. Everything shaking. The wolf’s body stretched impossibly, muscles bulging against skin, bones audibly scraping one another.

And then it was Cole, gasping, his lips tinged blue, his fingers jerking and reaching for air. I could still see his skin stretching and remaking itself along his ribs with each shuddering breath. His green eyes were half-lidded, each blink almost too long to be a blink.

I heard Isabel suck in her breath and I realized that I should have warned her to look away. I put my hand on her arm. She flinched.

“Are you okay?” I asked.

“I’m fine,” she replied, too fast to mean it. No one was fine after they saw that.

The next song on the CD started, and when the drums pattered an opening, one of NARKOTIKA’s best-known songs, Cole laughed, silently, a laugh that saw no humor in anything, ever.

Isabel stood up, suddenly ferocious, like the laugh had been a slap.

“My work here’s done. I’m going to go.”

Cole’s hand reached out and curled around her ankle. His voice was slurred. “IshbelCulprepr.” He closed his eyes; opened them again. They were slits. “Youknow what-do.” He paused. “Affer the beep. Beep.”

I looked at Isabel. Victor’s hands pounded posthumously on the drums in the background.

She told Cole, “Next time, kill yourself outside. Less cleanup for Sam.”

“Isabel,” I said sharply.

But Cole seemed unaffected.

“Was just,” he said, and stopped. His lips were less blue now that he’d been breathing for a while. “Was just trying to find …” He stopped entirely and closed his eyes. A muscle was still twitching over his shoulder blade.

Isabel stepped over his body and snatched up her purse from the couch. She stared at the banana I’d left there beside it, eyebrows pulled down low over her eyes as if, out of everything that she’d seen today, the banana was the most inexplicable.

The idea of being alone in the house with Cole — with Cole, like this — was unbearable.

“Isabel,” I said. I hesitated. “You don’t have to go.”

She looked back at Cole, and her mouth became a thin, hard thing. There was something wet caught in her long lashes. She said, “Sorry, Sam.”

When she left, she shut the back door hard enough to make every glass Cole had left on the counter rattle.

CHAPTER EIGHT

• ISABEL •

As long as I kept the speedometer needle above sixty-five, all I saw was the road.

The narrow roads around Mercy Falls all looked the same after dark. Big trees, then small trees, then cows, then big trees, then small trees, then cows. Rinse and repeat. I threw my SUV around corners with crumbling edges and hurtled down identical straightaways. I went around one turn fast enough that my empty coffee cup flew out of the cup holder. The cup pattered against the passenger side door and then rolled around in the footwell as I tore around another turn. It still didn’t feel fast enough.

What I wanted was to drive faster than the question: What if you’d stayed?

I’d never had a speeding ticket. Having a hotshot lawyer father with anger-management issues was a fantastic deterrent; usually just imagining his face when he heard the news kept me safely under the limit. Plus, out here, there wasn’t really any point to speeding. It was Mercy Falls, population: 8. If you drove too fast, you’d find yourself through Mercy Falls and out the other side.

But right now, a screaming match with a cop felt just about right for my current state of mind.

I didn’t head toward home. I already knew that I could get home in twenty-two minutes from where I was. Not long enough.

The problem was that he was under my skin now. I’d gotten close to him again and I’d caught Cole. He came with a very specific set of symptoms. Irritability. Mood swings. Shortness of breath. Loss of appetite. Listless, glassy eyes. Fatigue. Next up, pustules and buboes, like the plague. Then, death.

I’d really th

ought I’d recovered. But it turned out I was just in remission.

It wasn’t just Cole. I hadn’t actually told Sam about my father and Marshall. I tried to convince myself that my father couldn’t get the protection lifted from the wolves. Not even with the congressman. They were both big shots in their hometowns, but that was different from being a big shot in Minnesota. I didn’t have to feel guilty about not warning Sam tonight.

I was so lost in my thoughts that I didn’t realize my rearview mirror was full of flashing red and blue lights. The siren wailed. Not a long one, just a brief howl to let me know he was there.

Suddenly a screaming match with a cop didn’t feel like such a brilliant idea.

I pulled over. Got my license out of my purse. Registration from the glove box. Rolled down the window.

When the cop came to my window, I saw that he wore a brown uniform and the big weird-looking hat that meant he was a state trooper, not a county cop. State cops never gave warnings.

I was so screwed.

He shone a flashlight at me. I winced and turned on the interior light of the car so he’d turn it off.

“Good evening, miss. License and registration, please.” He looked a little pissed. “Did you know I was following you?”

“Well, obviously,” I said. I gestured to the gearshift, put it into park.

The trooper smiled the unfunny smile my father did sometimes when he was on the phone. He took my license and the registration without looking at them. “I was behind you for a mile and a half before you stopped.”

“I was distracted,” I said.

“That’s no way to drive,” the cop said. “I’m here to give you a citation for going seventy-three in a fifty-five zone, all right? I’ll be right back. Please don’t move your vehicle.”

He walked back to his car. I left the window open, even though bugs were starting to smack themselves against the strobe lights in my mirrors. Imagining my father’s reaction to this ticket, I fell back into my seat and closed my eyes. I’d be grounded. My credit card taken away. Phone privileges gone. My parents had all sorts of torture devices they’d concocted back in California. I didn’t have to worry about whether or not I should go see Sam or Cole again, because I would be locked in the house for the rest of my senior year.

“Miss?”

I opened my eyes and sat up. The trooper was by my window again, still holding my license and registration, a little ticket book beneath them.

His voice was different from before. “Your license says ‘Isabel R. Culpeper.’ Would that be any relation to Thomas Culpeper?” “He’s my father.”

The trooper tapped his pen against his ticket book.

“Ah,” he said. He handed me the license and the registration. “That’s what I thought. You were going too fast, miss. I don’t want to see you doing that again.”

I stared at the license in my hands. I looked back at him. “What about —?”

The trooper touched the brim of his hat. “Have a safe night, Miss Culpeper.”

CHAPTER NINE

• SAM •

I was a general. I sat awake for most of the night poring over maps and strategies of how to confront Cole. Using Beck’s chair as my fortress, I swiveled back and forth in it, scribbling fragments of potential dialogue on Beck’s old calendar and using games of solitaire for divination. If I won this game, I would tell Cole the rules by which he had to live to stay in this house. If I lost, I would say nothing and wait to see what happened. As the night grew longer, I made more complicated rules for myself: If I won but it took me longer than two minutes, I would write Cole a note and tape it to his bedroom door. If I won and put down the king of hearts first, I would call him from work and read him a list of bylaws.

In between solitaire games, I tried out sentences in my head. Somewhere, there were words that would convey my concern to Cole without sounding patronizing. Words that sounded tactful but persuasive. That somewhere was not a place I could imagine finding.

Every so often, I crept out of Beck’s office and down the dim gray hallway to the living room door, and I stood and watched Cole’s seizure-spent body until I was certain I had seen him take a breath. Then frustration and anger propelled me back to Beck’s office for more futile planning.

My eyes burned with exhaustion, but I couldn’t sleep. If Cole woke up, I might speak to him. If I’d just won a game of solitaire. I couldn’t risk him waking and me not speaking to him right away. I wasn’t sure why I couldn’t risk it — I just knew I couldn’t sleep knowing he might wake up in the interim.

When the phone rang, I started hard enough to make Beck’s chair spin. I let the chair complete its rotation, then cautiously picked up the receiver.

“Hello?”

“Sam,” Isabel said. Her voice was brisk and detached. “Do you have a moment to chat?”

Chat. I had a special brand of hatred for the phone as a chatting medium. It didn’t allow for spaces or silences or breaths. It was speaking or nothing, and that felt unnatural for me. I said, cautiously, “Yes.”

“I didn’t get a chance to tell you earlier,” Isabel said. Her voice was still the sharp, enunciated words of a telephone bill collector. “My father is meeting with a congressman about getting the wolves taken off the protected list. Think helicopters and sharpshooters.”

I didn’t say anything. It wasn’t what I thought she’d wanted to chat about. Beck’s chair still had some momentum, so I let it turn another time. My tired eyes felt like they were being pickled in my skull. I wondered if Cole was awake yet. I wondered if he was still breathing. I remembered a small, stocking-hatted boy being pushed into a snowbank by wolves. I thought about how far away Grace must be by now.

“Sam. Did you hear me?”

“Helicopters,” I said. “Sharpshooters. Yes.”

Her voice was cool. “Grace, shot through the head from three hundred yards.”

It stung, but in the way that distant, hypothetical horrors did, like disasters reported on the news. “Isabel,” I said, “what do you want from me?”

“What I always want,” she replied. “For you to do something.”

And in that moment, I missed Grace, more than I had during any time in the past two months. I missed her so hard that it actually did make me catch my breath, like her absence was something real stuck in the back of my throat. Not because having her here would solve these problems, or because it would make Isabel let me be. But for the sharp, selfish reason that if Grace were here, she would have answered that question differently. She would know that when I asked, I didn’t want an answer. She’d tell me to go sleep, and I would be able to. And then this long, terrible day would end, and when I woke up in the morning, everything would look more plausible. Morning lost its healing powers when it arrived and found you already wide-eyed and wary.

“Sam. God, am I talking to myself?” Over the line, I heard the chime cars made when a door was opened. And then a sharp intake of breath as the door shut.

I realized I was being an ingrate. “I’m sorry, Isabel. It’s just been — it’s been a really long day.”

“Tell me about it.” Her feet crunched across gravel. “Is he all right?”

I walked the phone down the hallway. I had to wait a moment to let my eyes adjust to the pools of lamplight — I was so tired that every light source had halos and ghostly trails — and waited for the requisite rise and fall of Cole’s chest.

“Yes,” I whispered. “He’s sleeping.”

“More than he deserves,” Isabel said.

I realized that it was time to stop pretending to be oblivious. Probably well past time. “Isabel,” I said, “what went on between you two?”

Isabel was silent.

“You aren’t my business.” I hesitated. “But Cole is.”

“Oh, Sam, it’s a little late to be pulling the authority card now.”

I didn’t think that she meant to be cruel, but it smarted. It was only by imagining what Grace had told me of Is

abel — of her getting Grace through my disappearance, when Grace had thought I was dead — that kept me on the phone. “Just tell me. Is there something going on between you two?”

“No,” Isabel snapped.

I heard the real meaning, and maybe she meant for me to. It was a no that meant not at the moment. I thought of her face when she saw the needle beside Cole and wondered just how big of a lie that no was. I said, “He’s got a lot to work through. He’s not good for anyone, Isabel.”

She didn’t answer right away. I pressed my fingers against my head, feeling the ghost of the meningitis headache. Looking at the cards on the computer screen, I could see that I had no more options. The timer said it had taken me seven minutes and twenty-one seconds to realize I’d lost.

“Neither,” Isabel said, “were you.”

CHAPTER TEN

• COLE •

Back on the planet called New York, my father, Dr. George St. Clair, MD, PhD, Mensa, Inc., was a fan of the scientific process. He was a good mad scientist. He cared about the why. He cared about the how. Even when he didn’t care about what it was doing to the subject, he cared about how you could state the formula to replicate the experiment.

Me, I cared about results.

I also cared, very deeply, about not being like my father in any way. In fact, most of my life decisions were based around the philosophy of not being Dr. George St. Clair.

So it was painful to have to agree with him on something so important to him, even if he’d never know about it. But when I opened my eyes, feeling like my insides had been pounded flat, the first thing I did was feel for the journal on the nightstand beside me. I had woken earlier, found myself alive on the living room floor — that was a surprise — and crawled to my bedroom to sleep or finish the process of dying. Now, my limbs felt like they’d been assembled by a factory with lousy quality control. Squinting in gray light that could’ve been any time of day or night, I opened the journal up with fingers that felt like inanimate objects. I had to turn past pages of Beck’s handwriting to get to my own, and then I wrote the date and copied the format I’d used on the days before. My handwriting on the facing page was a bit sturdier than the letters I scratched down now.

Lament: The Faerie Queens Deception

Lament: The Faerie Queens Deception Sinner

Sinner The Dream Thieves

The Dream Thieves All the Crooked Saints

All the Crooked Saints Shiver

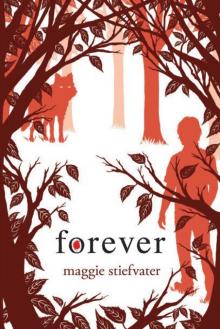

Shiver Forever

Forever The Raven King

The Raven King Opal

Opal Linger

Linger The Raven Boys

The Raven Boys The Scorpio Races

The Scorpio Races Hunted

Hunted Ballad: A Gathering of Faerie

Ballad: A Gathering of Faerie Call Down the Hawk

Call Down the Hawk Mister Impossible

Mister Impossible Wolves of Mercy Falls 03 - Forever

Wolves of Mercy Falls 03 - Forever Lament

Lament![Maggie Stiefvater - [Wolves of Mercy Falls 02] Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/04/maggie_stiefvater_-_wolves_of_mercy_falls_02_preview.jpg) Maggie Stiefvater - [Wolves of Mercy Falls 02]

Maggie Stiefvater - [Wolves of Mercy Falls 02] Lament: The Faerie Queen's Deception

Lament: The Faerie Queen's Deception Pip Bartlett's Guide to Magical Creatures

Pip Bartlett's Guide to Magical Creatures Ballad

Ballad