- Home

- Maggie Stiefvater

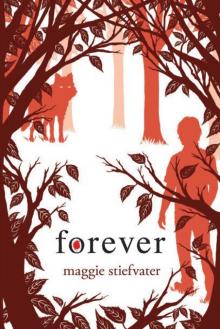

Wolves of Mercy Falls 03 - Forever

Wolves of Mercy Falls 03 - Forever Read online

forever

maggie stiefvater

For those who chose

“yes”

Ach der geworfene, ach der gewagte Ball,

füllt er die Hände nicht anders mit Wiederkehr:

rein um sein Heimgewicht ist er mehr.

Oh, the ball that’s thrown, the ball that dared,

Does it not fill your hands differently when it returns:

made weightier, merely by coming home.

—Rainer Maria Rilke

PROLOGUE

• SHELBY •

I can be so, so quiet.

Haste ruins the silence. Impatience squanders the hunt.

I take my time.

I am silent as I move through the darkness. Dust hangs in the air of the nighttime wood; the moonlight makes constellations of the particles where it creeps through the branches overhead.

The only sound is my breath, inhaled slowly through my bared teeth. The pads of my feet are noiseless in the damp underbrush. My nostrils flare. I listen to the beat of my heart over the sound of the muttering gurgle of a nearby creek.

A dry stick begins to pop under my foot.

I pause.

I wait.

I go slowly. I take a long time to lift my paw from the stick. I am thinking, Quiet. My breath is cold over my incisors. I hear a live, rustling sound nearby; it catches my attention and holds it. My stomach is tight and empty.

I push farther into the darkness. My ears prick; the panicked animal is close by. A deer? A night insect fills a long moment with clicking sounds before I move again. My heart beats rapidly in between the clicks. How large is the animal? If it’s injured, it won’t matter that I’m hunting alone.

Something brushes my shoulder. Soft. Tender.

I want to flinch.

I want to turn and snap it between my teeth.

But I am too quiet. I freeze for a long, long moment, and then I turn my head to see what is still brushing my ear with a feather touch.

It is a something that I can’t name, floating in the air, drifting in the breeze. It touches my ear again and again and again. My mind burns and bends, struggling to name it.

Paper?

I don’t understand why it is there, hanging like a leaf in the branch when it is not a leaf. It makes me uneasy. Beyond it, scattered on the ground, there are items imbued with an unfamiliar, hostile smell. The skin of some dangerous animal, shed and left behind. I shy away from them, lip curled, and there, suddenly, is my prey.

Only it is not a deer.

It is a girl, twisting in the dirt, hands gripping soil, whimpering. Where the moonlight touches her, she’s stark white against the black ground. Fear ripples off her. My nostrils are full of it. Already uneasy, I feel the fur at the back of my neck prickle and rise. She is not a wolf, but she smells like one.

I am so quiet.

The girl doesn’t see me coming.

When she opens her eyes, I am right in front of her, my nose nearly touching her. She was panting soft, heated breaths onto my face, but when she sees me, they stop.

We look at each other.

Every second that her eyes stay on mine, more fur raises along my neck and spine.

Her fingers curl in the dirt. When she moves, she smells less wolf and more human. Danger hisses in my ears.

I show her my teeth; I ease backward. All I can think of is retreating, getting only trees around me, putting space between us. Suddenly I remember the paper hanging in the tree and the shed skin on the ground. I feel fenced in — this strange girl in front of me, that alien leaf behind me. My belly touches underbrush as I crouch, tail tucked between my legs.

My growl starts so slowly that I feel it on my tongue before I hear it.

I am trapped between her and the things that smell like her, moving in the branches and lying on the ground. The girl’s eyes are on mine still, challenging me, holding me. I am her prisoner and I cannot escape.

When she screams, I kill her.

CHAPTER ONE

• GRACE •

So now I was a werewolf and a thief.

I’d found myself human at the edge of Boundary Wood. Which edge, I didn’t know; the woods were vast, stretching for miles. Easily traveled as a wolf. Not so easy as a girl. It was a warm, pleasant day — a great day, by spring-in-Minnesota standards. If you weren’t lost and naked, that is.

I ached. My bones felt as if they’d been rolled into Play-Doh snakes and then back into bones and then back into snakes again. My skin was itchy, especially over my ankles and elbows and knees. One of my ears rang. My head felt fuzzy and unfocused. I had a weird sense of déjà vu.

Compounding my discomfort was the realization that I was not only lost and naked in the woods, but naked in the woods near civilization. As flies buzzed idly around me, I stood up straight to look at my surroundings. I could see the backs of several small houses, just on the other side of the trees. At my feet was a torn black trash bag, its contents littering the ground. It looked suspiciously like it may have been my breakfast. I didn’t want to think about that too hard.

I didn’t really want to think about anything too hard. My thoughts were coming back to me in fits and starts, swimming into focus like half-forgotten dreams. And as my thoughts came back, I was remembering being in this moment — this dazed moment of being newly human — over and over again. In a dozen different settings. Slowly, it was coming back to me that this wasn’t the first time I’d shifted this year. And I’d forgotten everything in between. Well, almost everything.

I squeezed my eyes shut. I could see his face, his yellow eyes, his dark hair. I remembered the way my hand fit into his. I remembered sitting next to him in a vehicle I didn’t think existed anymore.

But I couldn’t remember his name. How could I forget his name?

Distantly, I heard a car’s tires echo through the neighborhood. The sound slowly faded as it drove by, a reminder of just how close the real world was.

I opened my eyes again. I couldn’t think about him. I just wouldn’t. It would come back to me. It would all come back to me. I had to focus on the here and now.

I had a few options. One was to retreat back into these warm, spring woods and hope that I’d change back into a wolf soon. The biggest problem with that idea was that I felt so utterly and completely human at the moment. Which left my second idea, throwing myself on the mercy of the people who lived in the small blue house in front of me. After all, it appeared I’d already helped myself to their trash and, from the look of it, the neighbors’ trash as well. There were a lot of problems with this idea, however. Even if I felt completely human right now, who knew how long that would last? And I was naked and coming from the woods. I didn’t know how I could explain that without ending up at the hospital or the police station.

Sam.

His name returned suddenly, and with it a thousand other things: poems whispered uncertainly in my ear, his guitar in his hands, the shape of the shadow beneath his collarbone, the way his fingers smoothed the pages of a book as he read. The color of the bookstore walls, how his voice sounded whispered across my pillow, a list of resolutions written for each of us. And the rest, too: Rachel, Isabel, Olivia. Tom Culpeper throwing a dead wolf in front of me and Sam and Cole.

My parents. Oh, God. My parents. I remembered standing in their kitchen, feeling the wolf climbing out of me, fighting with them about Sam. I remembered stuffing my backpack full of clothing and running away to Beck’s house. I remembered choking on my own blood….

Grace Brisbane.

I’d forgotten all of it as a wolf. And I was going to forget it all again.

I knelt, because standing seemed sudd

enly difficult, and clutched my arms around my bare legs. A brown spider crawled across my toes before I had a chance to react. Birds kept singing overhead. Dappled sunlight, hot where it came through full strength, played across the forest floor. A warm spring breeze hummed through the new green leaves of the branches. The forest sighed again and again around me. While I was gone, nature moved on, normal as always, but here I was, a small, impossible reality, and I didn’t know where I belonged or what I was supposed to do anymore.

Then, a warm breeze, smelling almost unbearably of cheese biscuits, lifted my hair and presented me with an option. Someone had clearly been feeling optimistic about this fair weather and had hung out a line of clothing to dry at the brick rambler next door. My eye was caught by the garments as the wind fluffed them. A line of neatly pinned-up possibilities. Whoever lived in the rambler was clearly a few sizes larger than me, but one of the dresses looked like it had a tie around the waist. Which meant it could work. Except, of course, it meant stealing someone’s clothing.

I had done a lot of things that a lot of people might not consider strictly right, but stealing wasn’t one of them. Not like this. Someone’s nice dress that they probably had to wash by hand and hang up to dry. And they had underwear and socks and pillowcases up on the line, too, which meant they were probably too poor to have a dryer. Was I really willing to take someone’s Sunday dress so I would have a chance at getting back to Mercy Falls? Was that really the person I was now?

I’d give it back. When I was done.

I crept along the woodline, feeling exposed and pale, trying to get a better look at my prey. The smell of cheese biscuits — probably what had drawn me as a wolf in the first place — suggested to me that someone must be home. No one could abandon that smell. Now that I’d caught the scent, it was hard for me to think of anything else. I forced myself to focus on the problem at hand. Were the makers of the cheese biscuits watching? Or the neighbors? I could stay mostly out of sight, if I was clever.

My unlucky victim’s backyard was a typical one for the houses near Boundary Wood, littered with the usual suspects: tomato cages, a hand-dug barbecue pit, television antennae with wires leading to nowhere. Push mower half covered with a tarp. A cracked plastic kiddie pool filled with funky-looking sand, and a family of lawn furniture with plasticky sunflower-printed covers. A lot of stuff, but nothing really useful as cover.

Then again, they’d been oblivious enough for a wolf to steal trash off their back step. Hopefully they were oblivious enough for a naked high school girl to nick a dress from their clothesline.

I took a deep breath, wished for a single, powerful moment that I could be doing something easy like taking a pop quiz in Calculus or ripping a Band-Aid off an unshaved leg, and then darted into the yard. Somewhere, a small dog began to bark furiously. I grabbed a handful of dress.

It was over before I knew it. Somehow I was back in the woods, stolen garment balled in my hands, my breath coming fast, my body hidden in a patch of what may or may not have been poison sumac.

Back at the house, someone shouted at the dog to Shut up before I put you out with the trash!

I let my heart settle down. Then, guiltily and triumphantly, I slid the dress over my head. It was a pretty blue flowered thing, too light for the season, really, and still a little damp. I had to cinch the back up quite a bit to make it fit me. I was almost presentable.

Fifteen minutes later, I had taken a pair of clogs off another neighbor’s back steps (one of the clogs had dog crap stuck to one heel, which was probably why they’d been put outside to begin with) and I was strolling along the road casually, like I lived there. Using my wolf senses, giving in like Sam had showed me so long ago, I could create a far more detailed picture of the surrounding area in my head than I could with my eyes. Even with all this information, I had no real idea where I was, but I knew this: I was nowhere near Mercy Falls.

But I had a plan, sort of. Get out of this neighborhood before someone recognized their dress and clogs walking away. Find a business or some kind of landmark to get my bearings, hopefully before the clogs gave me a blister. Then: somehow get back to Sam.

It wasn’t the greatest of plans, but it was all I had.

CHAPTER TWO

• ISABEL •

I measured time by counting Tuesdays.

Three Tuesdays until school was out for the summer.

Seven Tuesdays since Grace had disappeared from the hospital.

Fifty-five Tuesdays until I graduated and got the hell out of Mercy Falls, Minnesota.

Six Tuesdays since I’d last seen Cole St. Clair.

Tuesdays were the worst day of the week in the Culpeper household. Fight day. Well, every day could be a fight day in our house, but Tuesday was the surefire bet. It was coming up on a year since my brother, Jack, had died, and after a family screamathon that had spanned three floors, two hours, and one threat of divorce from my mother, my father had actually started going to group counseling with us again. Which meant every Wednesday was the same: my mother wearing perfume, my father actually hanging up the phone for once, and me sitting in my father’s giant blue SUV, trying to pretend the back didn’t still smell like dead wolf.

Wednesdays, everyone was on their best behavior. The few hours following counseling — dinner out in St. Paul, some mindless shopping or a family movie — were things of beauty and perfection. And then everyone started to drift away from that ideal, hour by hour, until, by Tuesday, there were explosions and fist-fights on set.

I usually tried to be absent on Tuesdays.

On this particular one, I was a victim of my own indecision. After getting home from school, I couldn’t quite bring myself to call Taylor or Madison to go out. Last week I’d gone down to Duluth with both of them and some boys they knew and spent two hundred dollars on shoes for my mother, one hundred dollars on a shirt for myself, and let the boys spend a third of that on ice cream we didn’t eat. I hadn’t really seen the point then, other than to shock Madison with my cavalier credit card wielding. And I didn’t see the point now, with the shoes languishing at the end of Mom’s bed, the shirt fitting weirdly now that I had it at home, and me unable to remember the boys’ names other than the vague memory that one of them started with J.

So I could do my other pastime, getting into my own SUV and parking in an overgrown driveway somewhere to listen to music and zone out and pretend I was somewhere else. Usually I could kill enough time to get back just before my mother went to bed and the worst of the fighting was over. Ironically, there had been a million more ways to get out of the house back in California, back when I hadn’t needed them.

What I really wanted was to call Grace and go walking downtown with her or sit on her couch while she did her homework. I didn’t know if that would ever be possible again.

I spent so long debating my options that I missed my window of opportunity for escape. I was standing in the foyer, my phone in my hand, waiting for me to give it orders, when my father came trotting down the stairs at the same time that my mother started to breach the door of the living room. I was trapped between two opposing weather fronts. Nothing to do at this point but batten the hatches and hope the lawn gnome didn’t blow away.

I braced myself.

My father patted me on my head. “Hey, pumpkin.”

Pumpkin?

I blinked as he strode by me, efficient and powerful, a giant in his castle. It was like I’d time-traveled back a year.

I stared at him as he paused in the doorway by my mother. I waited for them to exchange barbs. Instead they exchanged a kiss.

“What have you done with my parents?” I asked.

“Ha!” my father said, in a voice that could possibly be described as jovial. “I’d appreciate if you put something on that covered your midriff before Marshall gets here, if you’re not going to be upstairs doing homework.”

Mom gave me a look that said I told you so even though she hadn’t said anything about my shirt when I’d walke

d in the door from school.

“As in Congressman Marshall?” I said. My father had multiple college friends who’d ended up in high places, but he hadn’t spent much time with them since Jack had died. I’d heard the stories about them, especially once alcohol was passed around the adults. “As in ‘Mushroom Marshall’? As in the Marshall that boffed Mom before you did?”

“He’s Mr. Landy to you,” my father said, but he was already on his way out of the room and didn’t sound very distressed. He added, “Don’t be rude to your mother.”

Mom turned and followed my father back into the living room. I heard them talking, and at one point, my mother actually laughed.

On a Tuesday. It was Tuesday, and she was laughing.

“Why is he coming here?” I asked suspiciously, following them from the living room into the kitchen. I eyed the counter. Half of the counter was covered with chips and vegetables, and the other half was clipboards, folders, and jotted-on legal pads.

“You haven’t changed your shirt yet,” Mom said.

“I’m going out,” I replied. I hadn’t decided that until just now. All of Dad’s friends thought they were extremely funny and they were extremely not, so my decision had been made. “What is Marshall coming for?”

“Mr. Landy,” my father corrected. “We’re just talking about some legal things and catching up.”

“A case?” I drifted toward the paper-covered side of the counter as something caught my eye. Sure enough, the word I thought I’d seen — wolves — was everywhere. I felt an uncomfortable prickle as I scanned it. Last year, before I knew Grace, this feeling would’ve been the sweet sting of revenge, seeing the wolves about to get payback for killing Jack. Now, amazingly, all I had was nerves. “This is about the wolves being protected in Minnesota.”

“Maybe not for long,” my father said. “Landy has a few ideas. Might be able to get the whole pack eliminated.”

Lament: The Faerie Queens Deception

Lament: The Faerie Queens Deception Sinner

Sinner The Dream Thieves

The Dream Thieves All the Crooked Saints

All the Crooked Saints Shiver

Shiver Forever

Forever The Raven King

The Raven King Opal

Opal Linger

Linger The Raven Boys

The Raven Boys The Scorpio Races

The Scorpio Races Hunted

Hunted Ballad: A Gathering of Faerie

Ballad: A Gathering of Faerie Call Down the Hawk

Call Down the Hawk Mister Impossible

Mister Impossible Wolves of Mercy Falls 03 - Forever

Wolves of Mercy Falls 03 - Forever Lament

Lament![Maggie Stiefvater - [Wolves of Mercy Falls 02] Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/04/maggie_stiefvater_-_wolves_of_mercy_falls_02_preview.jpg) Maggie Stiefvater - [Wolves of Mercy Falls 02]

Maggie Stiefvater - [Wolves of Mercy Falls 02] Lament: The Faerie Queen's Deception

Lament: The Faerie Queen's Deception Pip Bartlett's Guide to Magical Creatures

Pip Bartlett's Guide to Magical Creatures Ballad

Ballad