- Home

- Maggie Stiefvater

Ballad Page 4

Ballad Read online

Page 4

The trow leaned toward another near him and said in his slow trow way, “It’s a leanan sidhe.”

And just like that, I had been announced. As insidious as the fast, primitive beat, the words were passed from dancer to dancer, and I felt eyes on me as I moved through the crowd. I was not just any solitary fey, I was the leanan sidhe. Lowest of the low. Nearly human.

“I didn’t know dancing was one of your talents,” called a faerie as she whirled by me. She and her friends were no taller than my hip, and their laughter stung like bees. I watched them spin for a moment, their feet falling unerringly with the driving drumbeat, until I saw her tail peek from under her gauzy green dress.

My smile was a snarl. “I didn’t realize talking was one of your talents. I didn’t think monkeys could speak.”

She jerked her dress down with a scowl in my direction and tugged the others away from me. I grimaced after them and kept making my way through the crowd. I didn’t know exactly what I was looking for—maybe just someplace where the music would finally pull me into its spell and make me forget the rest of this.

Someone grabbed my butt as I walked; by the time I spun, however, there was nothing but a row of grinning faces looking at me. It wasn’t that I couldn’t pick out the one who didn’t look innocent. More that I couldn’t find one who didn’t look guilty.

“Go screw yourselves,” I told them, and they all laughed.

“We’d like to, slut,” said one of them, and made a rude gesture. “Will you help?”

No point getting into a fight tonight. I just spit in their general direction and whirled away, putting as much distance between me and the butt-grabbers as I could.

The drum begged my feet to dance, but I didn’t. The music was gorgeous, and any other night I would’ve given into it. But tonight, all I could think about was what James and his pipes could do with the tune the musicians played now. I wasn’t sure why I’d bothered to come. I was a motionless island in the middle of a swirling sea of dancers. They didn’t bother to hide their stares as they rippled, spun, swayed with the music and with each other. There was laughter all around me.

“Are you lost, cailín?”

I’ll admit I was shocked shitless by both the kindness in the voice and the innocuous title—simply “girl” in Irish. I turned and found a man smiling down at me, dressed in court finery, his tunic buttoned with shell-shaped buttons all the way up his neck.

A human. He glowed vaguely golden, enough to make me hungry but not enough to really tempt me. Besides, though he was handsome enough, with his laugh-lined eyes and crooked nose, he was neither beautiful enough nor fair enough to be a changeling, stolen away by the faeries as a child. Between that and his court clothing, I would have bet my curls he was the queen’s new human consort. Even I, on the fringe as I was, had heard whispers of him.

I eyed him, wary, and said loftily, “Do I look lost, human?”

His eyes took in my jean skirt with the ripped bottom, my low-cut peasant top, and my impossibly tall cork heels. His mouth made a shape as if he had tried a lemon and found it sort of appealing. “It’s hard to imagine you anywhere you didn’t intend to be,” he admitted.

I curled my mouth into a smile.

“You have an extremely wicked smile,” he said.

“That’s because I am extremely wicked. Haven’t you heard?”

The consort’s eyes returned to my face and his already smile-thin eyes narrowed more. His voice was light, playful. “Should I have, human?”

I laughed out loud at his mistake. At least I knew now why he’d approached me—he thought I was one of his kind. Did I look that bad? “Far be it from me to disillusion you,” I replied. “You’ll find out soon enough. For now I’m enjoying your ignorance, to tell you the truth.”

“The truth is all anyone can speak around here,” the consort countered.

My mouth curled into a smile.

“I see conversing with you takes me only in circles,” he said, and he held out a hand. “Would you dance, instead? Just one dance?”

I didn’t like to dance with faeries, but he wasn’t one. My teeth were a thin white line. “There is no such thing as one dance inside this circle.”

“Indeed. So we dance until you say stop, and then—we stop?”

I paused. Dancing with Eleanor’s consort without begging for the privilege first seemed like a bad idea. Which added slightly to the appeal. “Where is my dear queen?”

“She is attending to other matters.” For half a second, I thought I saw something—relief, maybe—flicker across his face, and then it was gone. His hand was still outstretched toward me, and I put my hand in it.

And the music took us. My feet fell into the beat, and his feet were already in it, and we spun into the crowd. There was night somewhere out there, but it seemed far away from this hill, brilliantly lit by orbs and by the dust hanging in the air.

We were watched as we danced, his hands holding mine tightly, as if he held me up, and I heard voices as we danced past, snatches of conversation.

“—the leanan sidhe—”

“—if the queen knew—”

“—why does she dance with—”

“—he will be a king before—”

My fingers tightened on the consort’s. “So you will be a king; that’s why you are here.”

His eyes were bright. Like all humans, he was half-drunk with the music once he started to dance. “It is not a secret.”

I thought about saying it was from me, but I didn’t want to look like an idiot. “You’re only a human.”

“But I can dance,” he protested. And he could. Quite well for a human, the drum beat pushing his body this way and that, his feet making intricate patterns on the stamped-down grass. “And I will have magic, later, when I am king.” He spun me.

“How do you figure that, human?”

“The queen has promised me and I believe her; she can’t lie.” He laughed, wildly, and I saw that he was ravished by the music, thrilled with the dance, so very vulnerable to us. “She is very beautiful. It hurts me, cailín, how beautiful she is.”

That the queen’s beauty hurt him was no surprise to me. The queen’s beauty pained everyone who saw her. “Magic doesn’t just float around, human.”

He laughed again, as if what I had said was funny. “Of course not! It moves from body to body, right? So I suppose it shall come from another somebody.”

I considered myself a sinister creature but his statement sounded sinister, even to me. “Another magical somebody, hmm? One wonders how they would find another somebody like this. And what that would do to that somebody.”

“The queen is very cunning.”

I thought of the way she’d silently worked behind the old queen’s back, carefully making sure that when the old queen’s crown fell from her head, she—Eleanor—would rise up wearing it. “Oh, yes, she is very cunning. But it sounds to me like it’s going to be extremely painful to somebody else.”

The consort made a face of disbelief. “My queen is not cruel.”

I just looked at him. Surely he didn’t believe that. Not unless he’d been dropped on his head as a kid or something. But he didn’t take it back. So I said, “Not everyone can hold magic even when they can manage to find it.”

“Halloween, cailín. Day of the dead. Magic is more volatile then. And—she would not grant me something I could not carry. She knows my weaknesses. I am not afraid; I believe I will be one of you soon enough.”

“Stop,” I snarled, and I stopped so suddenly that he jerked my arm, twisting my shoulder uncomfortably. “I don’t think you know what you say.”

He dropped my hand and stood, arms slack by his sides. The dancers around us spun to stare at both of us. Their voices rose in murmurs and whispers.

“I would

n’t hurry to throw away my humanness so quickly,” I told him, widening the space between us. “Until you see what being faerie really means.”

My words were wasted. He just stared at me.

I left the consort standing there in the circle of faeries. Before I’d even gone halfway invisible, a tall, red-haired faerie had taken his hand, and by the time I had abandoned physical form entirely, riding up and up on human thoughts and dreams, the consort had been pulled into the dance once again. From overhead, I couldn’t tell him from the faeries, and I also couldn’t tell what emotion was burning in my chest. But I left them all behind, glad to be rid of them; I had a dream to bestow.

James

I dreamt of music.

A song, intoxicating and viral, from someplace far away, beautiful and unattainable.

I wanted it, this gray song of desire. It was real in a way no dream had ever been.

I knew this was Nuala’s doing, this song so beautiful that it hurt.

I woke up.

When I woke up, my mouth was stuffed with golden music. It was like having a song stuck in my head, but with taste and color and sensation attached to it. It was all wood smoke and beads of rain on oak leaves and shining gold strands choking me. It reminded me of wanting Dee, wanting to be a better piper, wanting to … just wanting.

“Hey, James. Wake up.” Paul’s voice pushed back the weight of the song, freeing my chest; I could breathe again. “It’s seven forty.”

I sucked in a deep breath of air that was comforting in its normalcy: vaguely unwashed laundry, stale Doritos, and old wood flooring. I had never properly appreciated the smell of Doritos—so human. I clung tightly to the humanness around me, a lifeboat in a sea of song. Paul’s words seemed vastly unimportant.

“Seven forty-one,” Paul said. His voice was accompanied by a zipper sound. His backpack, maybe. It pulled me further out of my dream; I tried not to resent him. “Are you awake?”

I was awake. It was just taking me a long time to claw my way out of sleep. I tried my voice and was a little surprised when it worked. “There is no way on God’s green earth that it’s seven forty. What happened to the alarm?”

“It happened fifteen minutes ago. Snooze button too. You didn’t even move.”

“I was dead,” I said, and sat up. My sheets were damp with sweat. “Dead people don’t move. Are you sure the alarm went off?”

I realized now he was fully dressed. He’d even had time to slick down his black hair with water, making him look like an Italian gangster. “It woke me up.” He peered at me, eyes round behind his glasses. “Are you sick?”

“Sick in the head, my friend.” I got out of bed; it felt like I was tearing myself out of a gauzy cobweb of dreams. Now that I was awake, I thought my bed smelled disconcertingly like Nuala’s breath had when I met her—all autumn and rain and wanting. Or maybe it was me, my skin. The thought was something like unpleasant. I wrenched my attention back to Paul. “But not ill in the conventional sense, I’m afraid. Do you think I can go to class like this?” I gestured to my T-shirt and boxers.

“Man, even I don’t want to see you like that. Are you coming to breakfast? You’ll have to hurry.”

I dug around on the floor for a cleanish pair of pants while Paul hovered by the door, unwilling to leave without me. I jerked on some clothing and scratched my hair into universal messiness. “Yes, I’m coming. Breakfast is the most important meal of the day, dear Paul. I wouldn’t miss it for the world. Do you think anyone will notice that I wore these yesterday?” Paul didn’t answer, wisely understanding the question to be rhetorical. “I’m ready. Let’s go—Wait.”

I knelt down and pulled my duffle bag from under the bed. Rummaging through the odds and ends in the bottom of it, I felt like I was answering an exam question.

Multiple choice #1: What in James’ duffle bag will help him ward off a supernatural menace with a very fine set of boobs?

a) a watch that doesn’t keep proper time

b) a novel—some horrible-looking space thriller—that his mother sent along, not realizing he would be spending every waking moment reading something some teacher had stuffed into his prone hands

c) a handful of granola bars, brought along in case of a nuclear holocaust and a subsequent lack of fresh food

d) an iron band that did absolutely jack-shit for him over the summer but seemed to work out for other people.

My fingers closed on the iron band—thin, uneven, with knobs on each end. I pulled it out. Paul wordlessly watched me as I fit the band around my wrist.

It had been weeks since the stain it left on my wrist had finally disappeared. I felt better with the iron against my skin. Protected, invincible.

I had always been an ace liar, even to myself.

I squeezed the knobs together until they pinched my skin. “Now I’m ready.”

Breakfast was as it always was. A bunch of music geeks collecting in the dining hall too early in the morning. Whoever had designed the dining hall had been clever, though; tall windows stretched from floor to ceiling on the east side. The morning sun flooded the room, illuminating the scratched wooden tops of the tables and the faded murals on the walls. At any other time of the day, the dining hall was mundane, dingy even. But first thing in the morning, blasted with first light, it was a friggin’ cathedral.

Conversation was muted and mostly drowned out by spoons in cereal bowls, forks moving through rubbery eggs. I stirred my cereal until it turned to paste, my mouth still full of the taste of the music in my dream.

“James, can I talk to you for a second? If you’re done eating?”

The voice was Sullivan’s. Most of the teachers who lived on campus ate later in a separate faculty room, away from us performing monkeys, but Sullivan often ate breakfast with the students. Since his class was first period, it made sense for him to be here at oh-dark-thirty. Plus, who else did he have to eat breakfast with, if not us?

“I’m holding court at present,” I told him.

Sullivan peered over his bowl of cereal at my table-mates. The usual suspects: Megan, Eric, Wesley, Paul. Everyone but the person I wanted. Couldn’t she even sit at my table anymore? Sullivan said, “Can you minions spare James for a moment?”

“Is he in trouble?” Megan had been babbling about British swear words, but she broke off to observe us.

“No more than usual.” Sullivan didn’t wait for an answer; he took my cereal and headed back toward an empty table, as if certain I would follow my breakfast.

“It appears my presence is desired by an authority figure.” I shrugged. I didn’t think they’d miss me; I was being terrible company anyway. “See you guys in class.”

I joined Sullivan and sat across from him. I wasn’t about to eat my pasty cereal, so I watched him carefully pick the nuts out of his. He had very long fingers with knobby joints. He was a very long person in general, with a rumpled appearance like he’d been thrown in the drier and then worn without ironing. This close, I could see that he was quite young. Thirties, tops.

“I heard about your piping instructor,” Sullivan said. The neat pile of nuts on his napkin toppled as he added another. “Or should I say, ‘ex-piping instructor’?” He lifted an eyebrow but didn’t look up from his careful sorting.

“Probably more appropriate,” I agreed.

“So, how are you liking Thornking-Ash?” He finally took a spoonful of cereal and began to eat. I could hear him crunching from where I sat; there wasn’t any milk in his bowl.

“Beats Chinese water torture.” Inexplicably, my eyes focused on the hand he held the spoon with. On one of his knobby fingers was a wide metallic ring, scratched with shapes. Ugly and dull, like the band on my wrist.

Sullivan caught my gaze. His eyes dropped briefly to my wrist and then back to his own ring. “Would you like to see it cl

oser?” He put down his spoon and began twisting his ring, working it over a knuckle.

A sick, uncertain melody sang in my ears, and in front of me Sullivan fell to the floor, then pushed himself onto his hands and knees, vomiting flowers and blood.

I squeezed my eyes shut for a second and then opened them. Sullivan was still working the ring off.

I shook my head. “No. Actually, I’d rather not. Please leave it on.”

The words were out before I could think of whether they sounded normal. In retrospect, they sounded like I was a head case, but Sullivan didn’t seem to notice. In any case, he kept the ring on.

“Well, you’re not an idiot,” Sullivan said. “I’m sure you know why I called you over here. We’re a music school, and you’ve basically graduated with honors before you’ve started. I looked up your stats. You had to know that we couldn’t possibly have an instructor of your level here.”

If I hadn’t confessed to my own flesh and blood why I’d come here, I wasn’t about to try it out on a random teacher. “Maybe I am an idiot.”

Sullivan shook his head. “I’ve seen enough to know what they look like.”

I wanted to grin. Sullivan was all right.

“Okay, so let’s assume I’m not an idiot.” I pushed my cereal out of the way and leaned on my arms. “Let’s assume I knew that I wasn’t going to find the piping equivalent of Obi-Wan here. Let’s also assume, for convenience’s sake, that I’m not going to tell you why I came, assuming I even had a good reason.”

“Let’s do that.” Sullivan glanced at the clock and then back at me. He had an intensity to his eyes that I was unfamiliar with in teachers; he wasn’t just another runner on the giant treadmill of adult life. “I’ve asked Bill what he thought I should do with you.”

It took me a moment to remember that Bill was the piping instructor.

“He thought I should just leave you be. You know, let you practice whenever you’d normally be taking your lesson, and leave it at that. But I think that sort of perverts the whole idea of having you come to a music school. Do you concur?”

Lament: The Faerie Queens Deception

Lament: The Faerie Queens Deception Sinner

Sinner The Dream Thieves

The Dream Thieves All the Crooked Saints

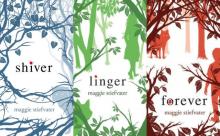

All the Crooked Saints Shiver

Shiver Forever

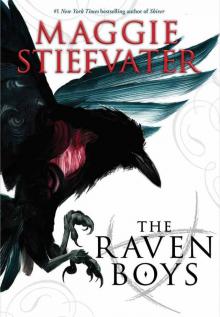

Forever The Raven King

The Raven King Opal

Opal Linger

Linger The Raven Boys

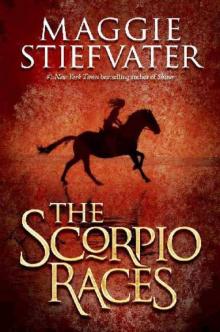

The Raven Boys The Scorpio Races

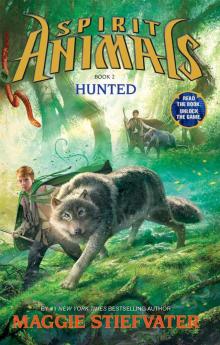

The Scorpio Races Hunted

Hunted Ballad: A Gathering of Faerie

Ballad: A Gathering of Faerie Call Down the Hawk

Call Down the Hawk Mister Impossible

Mister Impossible Wolves of Mercy Falls 03 - Forever

Wolves of Mercy Falls 03 - Forever Lament

Lament![Maggie Stiefvater - [Wolves of Mercy Falls 02] Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/04/maggie_stiefvater_-_wolves_of_mercy_falls_02_preview.jpg) Maggie Stiefvater - [Wolves of Mercy Falls 02]

Maggie Stiefvater - [Wolves of Mercy Falls 02] Lament: The Faerie Queen's Deception

Lament: The Faerie Queen's Deception Pip Bartlett's Guide to Magical Creatures

Pip Bartlett's Guide to Magical Creatures Ballad

Ballad